Food and the Spirit of Zen

Dogen's Teachings: The Tenzo Kyokun:“Instructions for the Cook”

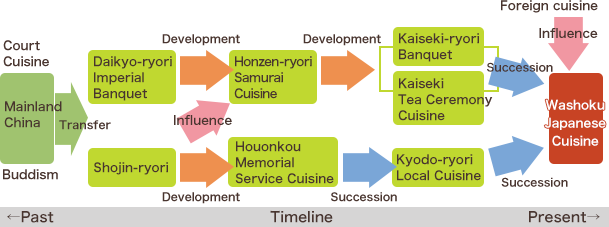

When we search for the roots of traditional Japanese cuisine, or washoku, we find that it can be traced back to China, from where it came into Japan over multiple time periods. The Heian Period saw a rise in imperial banquet style meals due to the influence of the Tang Dynasty, and fried foods such as karaage fried chicken, fried-then-boiled cuisine, and certain types of pastries were adopted during this period as well. However, the simple presentation of the foods of those days cannot be compared with today’s more complex and elegant dishes.

When we search for the roots of traditional Japanese cuisine, or washoku, we find that it can be traced back to China, from where it came into Japan over multiple time periods. The Heian Period saw a rise in imperial banquet style meals due to the influence of the Tang Dynasty, and fried foods such as karaage fried chicken, fried-then-boiled cuisine, and certain types of pastries were adopted during this period as well. However, the simple presentation of the foods of those days cannot be compared with today’s more complex and elegant dishes.

What caused this dramatic shift from simple to complex cuisine? The answer can be found by looking at the rise of Zen Buddhism during the Kamakura Period. Buddhist monks subsist on shojin-ryori, traditional Buddhist cuisine that, adhering to the principle of “non-killing,” is strictly vegetarian. In Zen Buddhism, the jobs of growing and preparing this food are designated as important monastic training practices.

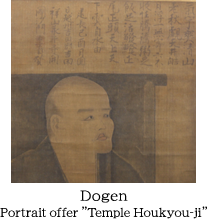

Fukui’s long history with shojin-ryori can be traced to the Soto Sect Head Temple Eihei-ji where, in the second year of the Kangen era (1244), shojin-ryori was established alongside the temple itself by Dogen, founder of the Soto sect of Zen Buddhism. At Eihei-ji, Dogen clarified the duties of the head chef, respectfully referred to as the Tenzo, and wrote a book on these duties entitled “Instructions for the Cook.” This book outlined the proper methods of cooking shojin-ryori imbued with the “Three Virtues and Six Flavors.” In simple terms, this style of cooking treats both the ingredients and those who receive the final product with the utmost level of respect, and through this process, simultaneously gives thanks to all creation. Due to the applicability of Soto Zen practices in everyday life, these teachings were absorbed by the greater populace and spread throughout society with relative ease.

To truly understand washoku’s origin, one must take a step back and first understand the food of Fukui. This culinary history can still be seen at Eihei-ji Temple, where shojin-ryori, the predecessor to washoku, continues to be made with care even today.

| Era | Representative Cuisine Style | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Heian | Daikyo-ryori Imperial Banquet Style | Aristocratic cuisine influenced by Tang culture, with a simple cooking process. |

| Kamakura | Shojin-ryori Buddhist Cuisine | Cuisine that adheres to the Tenzo Kyokun, or "Instructions for the Cook" penned by Dogen, founder of the Soto Sect of Zen Buddhism. |

| Muromachi | Honzen-ryori Samurai Cuisine | Samurai household hospitality cuisine, involving a cooking process that brings out the ingredients’ natural flavors. |

| Sengoku | Kaiseki Tea Ceremony Cuisine | Made to complement the enjoyment of tea, this cooking style adheres to rules such as "One Soup, Three Dishes.” |

| Edo | Kaiseki-ryori Banquet Cuisine | Banquet-style cuisine emphasizing sake and fish, following the philosophy of “Three Soups, Eleven Dishes” for a wide variety of dishes and arrangements. |

The Tenzo Kyokun:“Instructions for the Cook”

This cooking philosophy was brought to Japan by Dogen, along with Zen Buddhism itself. These teachings would become the foundation for washoku Japanese traditional cuisine.

“Three Virtues, Six Flavors”

Three Virtues : “Light and mild,” ”Pure and clean,” and “Adhering to etiquette.”

Six Flavors : “Spicy,” ”Sour,” ”Sweet,” ”Bitter,” “Salty,” and ”Tender.”

The Three Virtues form the basic attitude toward cooking:

・A light appearance and flavor

・Pure and fresh

・Made according to the correct etiquette

When these virtues harmonize with the Six Flavors, they form the essence of Shojin-ryori Soto Zen cuisine.

According to Dogen’s teachings, preparing food was a Zen training practice of the utmost importance, and simply using the Three Virtues and Six Flavors in cooking did not guarantee success unless the proper work ethic and labor was also applied.

The Basic Cooking Methods of Washoku:

Five Methods : Raw, boiled, baked, fried, and steamed

Five Flavors : Spicy, sour, sweet, bitter, and salty

Five Colors : Green, yellow, red, white, and black